Since our founding in 1844, Meadville Lombard has been forming leaders of all races, many ethnicities, and nationalities, who usher in spiritually grounded social change through ministries and faith formation.

Read A Brief History of Meadville Theological School of Lombard College, by Dr. Nicole Kirk, our Rev. Dr. J. Frank and Alice Schulman Professor of Unitarian Universalist History. [Below]

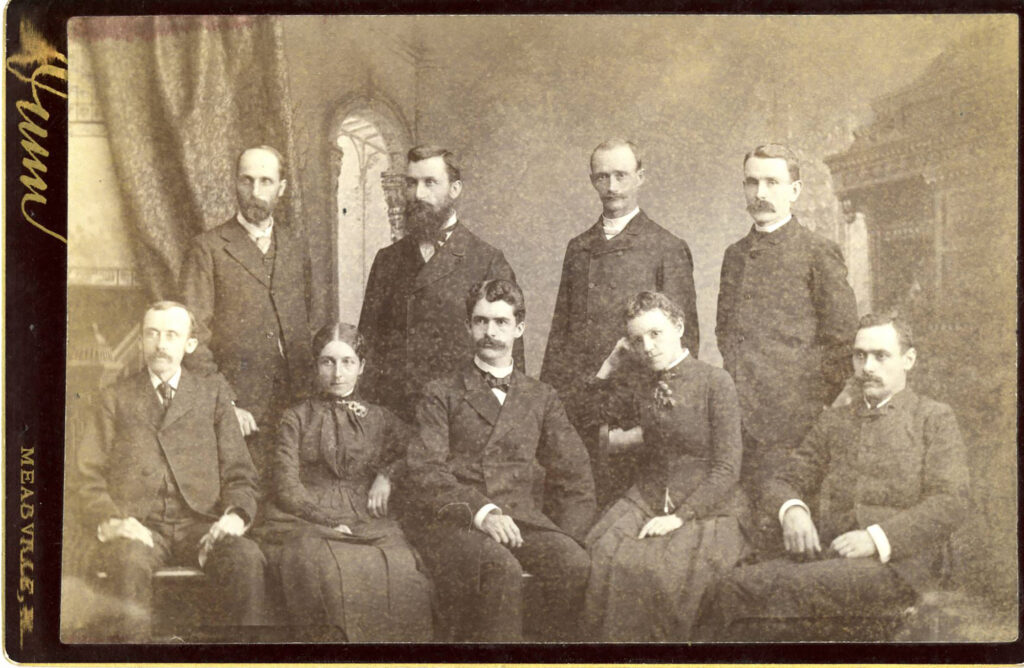

In 1882, at the age of thirty-two, Marion Murdock entered Meadville Theological Seminary in western Pennsylvania. She had been preparing for ministry since she was eight years old. She attended school followed by several years teaching and participating in Unitarian summer institutes until she felt ready to pursue ministry. Marion was not the first woman to take classes at the small Unitarian seminary in Pennsylvania. But Marion would be the first woman to graduate from the school, earning a Bachelor of Divinity in 1885.

A wave of women followed her, including Florence Buck, who would become Marion’s co-minister and life partner. Florence was the first woman to receive an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree from Meadville.

Marion Murdock was an American minister in Iowa. Murdock was said to be the first woman in America to receive the degree of Bachelor of Divinity.

Murdoch was educated at Northwestern Ladies’ College, Evanston, Illinois, and the University of Wisconsin.

Marion Murdock was an American minister in Iowa. Murdock was said to be the first woman in America to receive the degree of Bachelor of Divinity.

Murdoch was educated at Northwestern Ladies’ College, Evanston, Illinois, and the University of Wisconsin.

After graduation from Boston University School of Oratory, she spent several years teaching in Dubuque, Iowa, and Omaha, Nebraska. During that time, she was engaged in institute work each summer, thus developing a reputation in her own state. On deciding to take up the ministry, she entered the School of Liberal Theology in Meadville, Pennsylvania, in 1882. She graduated and took her degree, B. D., from the same school in 1885.

Her active labor in the ministry began while she was still in theological school. She occupied pulpits during school vacations, and occasionally during the school year. After completing her theological course, she was called to Unity Church, Humboldt, Iowa, and remained there five years. Under her management, it became the largest church in the area. She was minister of the First Unitarian Church in Kalamazoo, Michigan, for one year, after which she returned to Meadville Theological School and took a year of post-graduate work. In 1892, she went abroad to take a year’s course of lectures at Oxford University. She was at one time professor of mathematics and oratory at the University of Wisconsin.

From the first her ministry was successful. Her training under Prof. Monroe made her an eloquent speaker. Murdock was essentially a reformer, preaching upon questions of social, political, and moral reform. While decided in conviction, she was liberal and generous to opponents of her views.

She was popular and active in the social life of her church. She was involved in clubs and study-classes and led Shakespeare classes.

When Marion arrived at Meadville, the school had moved far beyond its humble origins in the basement of a house with one professor to a multi-building campus. As early as 1827, American Unitarians dreamed of establishing a seminary in the West to serve the needs of newly minted congregations. Early attempts to start a school in burgeoning western cities had failed. The idea to plant a seminary in the small town of Meadville, Pennsylvania, emerged out of a network of relationships among Unitarian lay leaders and ministers and the support of a vice president of the American Unitarian Association, Harm Jan Huidekoper.

An immigrant from Holland, Harm Jan Huidekoper arrived in Meadville in 1805 as an agent of the Holland Land Company. The company had acquired millions of acres through a series of treaties that had defrauded Native American tribes of their land, which was then sold for a profit and colonialized by settlers.

Florence Buck was born July 19, 1860. A lifelong companion/partner of Rev. Marion Murdock, the Unitarian minister in Kalamazoo, Michigan, she eventually attended Meadville Theological School and was ordained to the Unitarian ministry.

Rev. Buck and Rev. Murdock were called as co-pastors of Unity Church (First Unitarian Church) in Cleveland, Ohio, and served there for six years, 1894-1900 — the first women to hold a joint ministry in the United States. Buck was minister of the Unitarian Church in Kenosha, Wisc., 1901-10. After Murdock retired for health reasons, Revs. Murdock and Buck moved to California seeking a healthier climate. Buck served Unitarian Churches in Palo Alto, 1910, and Alameda, 1911-12.

Meadville Theological School conferred an honorary Doctor of Divinity degree on Buck in 1920. She was the first woman to receive this honor. In 1923 she was the first woman to preach at King’s Chapel in Boston. In 1925 she was the first woman to be named Executive Secretary of the AUA Department of Religious Education.

Buck died in Boston of typhoid fever. When the AUA built a new building in 1927, one of the rooms was named the Florence Buck Memorial Room. Funds for furnishing the room came from those who loved her, including many children, as a “tribute of respect and affection.”

Harm moved from managing the land to purchasing remaining parcels from the Holland Land Company—his real estate speculation and investments made him a wealthy man.

After converting to Unitarianism, Harm gathered a Unitarian church in Meadville in 1829 and hired Unitarian tutors from Harvard to tutor his five children and minister to the congregation.

Leaders of the Christian Connection, a type of Unitarian Baptists, were also interested in starting a seminary and committed to joining the Unitarians in their endeavor. While the Christian Connection offered little financial support, several elders of the movement served on the board, and—more importantly—they sent students. Faculty member David Millard was the sole Christian Connection professor. For the first decade of Meadville’s history, nearly half of every entering class was comprised of Christian Connection students. From the beginning, Meadville Seminary offered an education without doctrinal tests that welcomed a variety of liberal Christians, Universalists, and a large number of international students from the Christian Connection.

Starting in 1871, Meadville welcomed African American students from the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church and AME Zion; however, it was not until 1906 that the school granted a degree to its first African American graduate and Unitarian, Don Speed Smith Goodloe. Other African American students followed but frequently encountered a lukewarm reception. The large enrollment of international students contributed to the school’s success. Over time, students from Japan and the Brahmo Samaj in India also began attending the school. The Cruft Fellowship allowed Meadville students to study in Europe for a year.

The founding of Meadville was a family affair. While Harm donated money, he also doggedly raised an endowment, and served as the school’s first board president until his death in 1854.

Don Speed Smith Goodloe is the first African American Meadville graduate.

By the early 1920s, Don Speed Smith Goodloe had accomplished many of his life’s professional goals. During his eleven-year tenure in Bowie, he established a faculty of ten members, student enrollment of 80, an admission requirement of completion of seventh grade, the model elementary school for student teachers at Horsepen Hill School– the first school for black children in Bowie–a summer session, a new dormitory for women, and renovation of living quarters for men. He added one additional year to the course, which led to a second-grade certificate and permitted students to do two years additional work to earn a first-grade certificate.

Goodloe made many pleas for additional funding before the legislature in Annapolis–money that might have brought more rapid development to the school–but the state’s appropriations favored the white normal schools. Little is known about why Goodloe resigned his post in 1921 at the age of 43. He told a friend that he stepped down because he was simply tired of being principal. It is possible that he was weary of the struggle to find sufficient funding that would enable him to upgrade the curriculum to the standards used at Maryland’s white normal schools in Towson and Frostburg. It was also quite likely that he was tired of dealing with racism and segregation and the inequality of the times and wished to immerse himself in the black community. The Ku Klux Klan was reviving in the South and across Middle America. There were 64 lynching’s in 1918 and an astounding 83 the following year. There were at least fourteen blacks hanged by mobs in Maryland in the 20 years before Goodloe arrived and two during his tenure at Bowie.

Perhaps Goodloe simply gave up on Booker T. Washington’s dream of gaining equality with whites through hard work, patience, and acceptance of the prevailing social order. It is possible that he had come to accept the call of the more militant W.E.B. Dubois to reject a legal, political, and economic system that thrived on the exploitation of poor African Americans.

After leaving the school, Goodloe moved to Baltimore, where in 1923 he became president of an insurance company, the Standard Benefit Society. He grew prosperous enough to purchase rental housing in the city. Later, he moved to Washington, and it is reported that he owned extensive property in the District. Meanwhile, Fannie and the children continued to live in the house in Bowie. Wallis and Donald both graduated from Howard University, became teachers in Baltimore, and later in Washington. Donald B. Goodloe taught at Washington’s Dunbar High School; one of his former students, William C. Byers, is currently a member of the Goodloe Memorial Unitarian Universalist Congregation.

Although there is no record of Goodloe’s religious affiliation after Meadville, his religious leanings did have an effect on his children. One of his sons, Donald B. Goodloe, was an active member at All-Souls Church, Unitarian in Washington.

Don Speed Smith Goodloe died in Washington, D.C. in 1959 at the age of 81. His legacy lives on in Bowie. Goodloe’s enormous contributions to the building of Bowie State University will not be forgotten, and members of Goodloe Memorial Unitarian Universalist Congregation will remember him as one of the early Bowie pioneers.

Goodloe’s life as an educator remains forever consistent with the Unitarian Universalist principles that espouse a belief in the inherent worth and dignity of every person; justice, equity and compassion in human relations; a free and responsible search for truth and meaning; the right of conscience and the use of the democratic process within our congregations and in society at large; the goal of world community with peace, liberty, and justice for all; and respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part.

—From UU Sankofa slides, by Dick and Barbara Morris, January 2005

Four of his children made significant contributions to the success of the school. Siblings Alfred and Elizabeth Huidekoper made regular donations to the school and served on the Board of Trustees for decades. Edgar Huidekoper served as school treasurer for eighteen years and also as superintendent of Divinity Hall. Frederic Huidekoper, a graduate of Harvard and ordained as a minister-at-large, at the urging of friends agreed to serve as the first professor for the new school. In addition, Frederic gifted his impressive collection of theological texts as the school’s first library. The arrival of Rufus Stebbins provided the school with a president and its second professor. Stebbins felt called to make Meadville the “new school of the prophets.” An abolitionist, Rufus brought additional support to the small part that Harm and the seminary played in Meadville’s Underground Railroad, led by the local leader, Richard Henderson.

In 1851, seven years after Meadville’s founding and 609 miles to the west in the small village of Galesburg, Illinois, a group of Universalists felt a need to open a secondary school for their children. Universalists had experienced a “spirit of intolerance” for their beliefs and discovered their children were being taught “creeds they deemed untrue.” By the fall of 1852, Universalist leaders welcomed their first students at the coeducational Illinois Liberal Institute. The Institute shifted to collegiate instruction a few months later.

The school’s early momentum was thwarted when the main building burned to the ground in the spring of 1855. A significant donation by Benjamin Lombard Sr. saved the school from closing and the school was renamed Lombard University. The school rebuilt and developed a beautiful campus graced with hundreds of trees. The graduating class of 1868 planted an elm to commemorate their classmates who served and died during the Civil War. Over the years, the elm grew into a towering tree that became known as the “Lombard Elm,” or “Big Ben.” Under this magnificent tree, generations of students gathered for school rituals and ceremonies.

Lombard University became Lombard College in 1900. Despite a beautiful, tree-lined campus and a variety of programs, the school floundered. By 1915, the student body shrank to thirty students, and school administrators began merger talks with nearby Knox College, but the plan fell apart. By the 1920s, the pattern of scarcity was taking a toll, and the Universalists reached out to the Unitarians for assistance. A large infusion of cash and Unitarian leadership was not enough to keep the doors open; in 1930, Lombard College held its last graduation exercises.

Lombard had opened a divinity department in 1881 to train ministers, explaining that “the pressing need of the West is Missionaries, who will go into our growing cities and towns.” The department expanded and became Ryder Divinity School in 1890 when a prominent minister left a bequest for the school. The divinity school, which welcomed women as students, was moved to Chicago in 1912 to offer more opportunities to students as part of the University of Chicago campus. In partnership with the Hyde Park Universalist congregation, a new building was constructed. Ultimately, the changes did not increase enrollment, and eventually Ryder merged with Meadville.

Meadville Theological Seminary was not immune to the University of Chicago’s pull either. A joint effort between the school’s president, Franklin Southworth; the newly hired Hackley Professor of Sociology and Ethics, Dr. Anna Garlin Spencer; and the Unitarian Layman’s League of Chicago sponsored summer programs for Meadville students that gave them access to the University of Chicago and allowed faculty to create an Institute of Social Service and Social Reform. Later, Meadville’s board shuttered its undergraduate program, sending its students to complete their work at the University of Chicago instead. Over time, the ongoing connections to Chicago grew too strong to ignore, and Meadville’s board voted to move the seminary.

The school constructed a new building at 57th and Woodlawn, kitty-corner from the First Unitarian Church of Hyde Park; it was completed in 1930. Other school owned adjacent properties formed the new campus. By 1943, Meadville joined the Federated Faculty of the University of Chicago—an arrangement that lasted until the 1960s. Other dynamic programs followed, including the Modified Residency Program, the development of the Sankofa and Angus MacLean Religious Education archives, and more recently the establishment of special collections for women, humanists, Latinx, and global UU and U/U.

The innovation and creativity that marked much of Meadville Lombard’s history continued in 2011 when the school recreated itself. Leaving behind the residential seminary model, the school sold its buildings in Hyde Park and moved to the LEED-certified Spertus building in Chicago’s South Loop. In conjunction with the move, the faculty developed a new low-residency model rooted in contextual learning for the formation of resilient religious leaders capable of leading change in multiracial, multiethnic, and multifaith settings. The school also revitalized The Fahs Center by creating The Fahs Collaborative as an experiential laboratory for faith formation leadership, programming, and the creation of groundbreaking curricula such as the powerful Beloved Conversations: Meditations on Race and Ethnicity. The school’s changes drew the largest entering classes to Meadville Lombard in its history.

Over the last five years, Meadville Lombard has continued its pace of innovation by introducing new degree programs, expanding its global education initiatives, committing to dismantling white supremacy, and widening our reach to students in diverse communities. These shifts enabled the school to prepare agile leaders capable of responding deliberatively and creatively to theological, generational, cultural, environmental, and political trends that impact religious life, and in particular, challenges to racial and gender inclusion and equity, immigration, sexual orientation, and global consciousness. The good work continues.